Published in the May 2017 edition of China Today

By THOMAS S. AXWORTHY

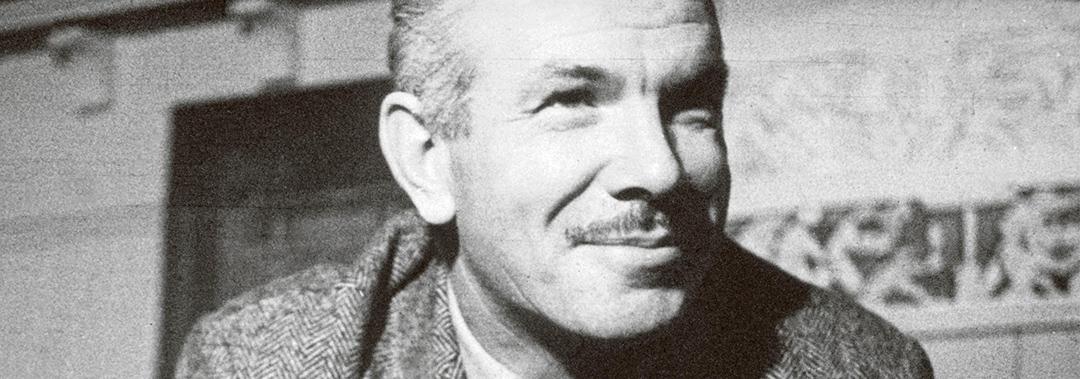

Norman Bethune is the best known Canadian in the world, according to Adrienne Clarkson, a former governor general of Canada and herself of Chinese descent. This is so because Bethune is a hero of China’s revolutionary era, immortalized by Mao Zedong in his December 21, 1939 essay “In Memory of Norman Bethune.” Bethune had died six weeks previously in Huangshikou, Hebei Province, after cutting his finger accidentally during an operation. The wound became infected and he died of septicemia, age 49.

Mao wrote of Bethune, “He made light of traveling thousands of miles to help us in our war of resistance against Japan. He arrived in Yan’an, in the spring of last year, went to work in the Wutai Mountain and to our great sorrow died a martyr, at his post. What kind of spirit is this that makes a foreigner selflessly adopt the cause of the Chinese people’s liberation as his own?” Mao further instructed that “we must all learn the spirit of absolute selflessness from him.” Today we should ask the same question as Mao Zedong in 1939.

What can we learn from Norman Bethune’s example and thoughts to help China and the world cope with the problems of 2017?

Dedicated Doctor and Internationalist

Bethune was born in 1890 in Gravenhurst, Ontario, Canada. He was the son of Christian missionaries and was named after his grandfather, Norman, the founder of the Upper Canada School of Medicine. Bethune rejected the theology of his parents, but not their crusading zeal. As a young man he put himself through university by working as a lumberjack in northern Ontario during the day and in the evenings he helped immigrant laborers learn English as a member of Frontier College.

In 1914, World War I broke out and Bethune suspended his medical studies at the University of Toronto to become a stretcher bearer in the Canadian Army’s No. 2 field ambulance unit. Severely wounded at the Battle of Ypes in 1915, Bethune’s experience in the war led him to emphasize the importance of treating the wounded as close to the front as possible rather than carrying them long distances back to hospitals, because so many died en route. He later put these insights to good use in Spain and China where he introduced the use of mobile blood transfusion units on the frontlines. Mobile army surgical hospital (MASH) units are now a standard feature of every army’s medical team.

After the war, Bethune earned accreditation at the Royal College of Surgeons and moved to Detroit to set up a successful private practice. Here he contracted tuberculosis, one of the most widespread and deadly diseases of the era. Bethune insisted on a new radical treatment called pneumothorax which involved artificially collapsing the diseased lung. This was a life-changing moment. Bethune became a specialist in thoracic surgery and the treatment of tuberculosis. He even sent out Christmas cards wishing everyone “Happy Pneumothorax!” By the end of the 1930s approximately half of the patients in Canadian sanatoriums underwent this procedure.

This near death experience with tuberculosis changed his life. He told friends that selfishness and avarice had ruled his life as a doctor but that “Now, in whatever time is left to me, I’m going to look around until I find something I can do for the human race, something great, and I’m going to do it before I die.” He re-dedicated his life to eradicating the “white plague” of tuberculosis which had nearly taken his own life. Tuberculosis occurred in epidemic proportions in the early years of the 20th century: 48,000 people contracted the disease every year in Canada, including my mother, who had to spend a year recovering in a sanatorium in Saskatchewan. In Canada, during this period, one out five patients admitted to a sanatorium died of the disease (in Quebec in 1925, for example, 3,000 people lost their lives to tuberculosis).

Bethune went to Montreal, Quebec,in 1928 to practice thoracic surgery at the Royal Victoria Hospital (a major institution affiliated with McGill University) and in 1933 he became chief of pulmonary surgery at the Hospital du Sacre-Coeur, also serving as a consultant to the hospital in Sherbrooke. While in Quebec, as he studied the causes of tuberculosis which were directly related to poverty and housing quality, he became more engaged in the politics of health. He often repeated a saying from his time in the Saranac Lake sanatorium that “there is a rich man’s tuberculosis and a poor man’s tuberculosis. The rich man recovers and the poor man dies.”

He campaigned publicly for hospital insurance and public investment in tuberculosis treatment, becoming one of the first doctors in Canada to advocate Medicare – but there was little response from either the medical establishment or the governments of the day. Increasingly radicalized, he joined the Communist Party of Canada in November 1935 and began signing his letters “Comrade Beth.” Soon after joining the party he volunteered to join the Loyalist government of Spain in fighting against the fascist insurrection and upon returning to Canada in 1938, he went to China to support Mao Zedong in the war against Japanese imperialists.

One Who Always Enlightens Us

My mother-in-law, Anne Carpenter, knew and worked with Bethune during the 1930s in Quebec. Born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, the youngest of six girls, Anne demonstrated an adventurous spirit by moving to Quebec to practice in Sherbrooke soon after graduating as a nurse in Manitoba. At that time, it was not common for young women to move half a continent away to take a job or practice a profession, certainly not in Quebec where a great majority of the citizens spoke French. Dr. Wendell MacLeod, a colleague of Bethune, wrote that women did not have an easy time of it in the Montreal medical establishment of the day. It was not until 1922 that the first woman intern in medicine was accepted and when the second woman to become an intern was asked to take over ward patients, she was relegated to the room reserved for alcoholics. Women physicians were not admitted to the doctors’ dining room until 1942! This was the medical world that greeted Anne Carpenter as a young female professional.

Anne’s assessment of Bethune was succinct: “brilliant but difficult,” she told me. Her judgment has been vindicated by a score of historians. Brilliant, Bethune certainly was. He invented or re-designed 12 medical and surgical instruments, some of which are still used today. He wrote a score of research papers and delivered them to professional associations across North America. He had the temperament of an artist and painted murals while resting in the sanatorium in the 1920s while he was recovering from tuberculosis. Later, he established an art school in Montreal for underprivileged students. He wrote poetry and his composition, Red Moon , is a haunting story of death in Spain. He was a dynamic speaker who spoke to thousands of Canadians and Americans on a transnational tour in 1937, sounding the alarm about the threats of fascism. And while in Spain, he made several radio broadcasts to North America. He was a brilliant communicator in addition to being a brilliant surgeon.

But he was difficult in equal measure. He always treated his patients with sensitivity and concern, and he established health clinics where he treated those who could not afford to pay. Yet the same generosity was not extended to his colleagues: he was impatient with nurses and doctors during operations and a colleague remembers him even throwing instruments in a fit of anger.

Bethune still serves as an exemplar of the revolutionary spirit. Once he had found his mission in life – first to eradicate tuberculosis, then to fight Fascists in Spain and finally to fight the Japanese imperialists in China – he performed extraordinary feats. In April 1939 for example, during the battle of Qihui, led by General He Long against the Japanese, Bethune and his team performed 115 operations in just 69 hours! Even in his own time, he became a legend to the soldiers of the Eighth Route Army.

But Bethune is more than just a historical artifact. In the 1920s, he made the connection between the tuberculosis in his patients and the wider social and political ills of poverty, societal degradation degradation and inequality. To use modern phraseology, he was an early practitioner of the “social determinants of health.”

Today he would make the connection between the health of the environment and our individual wellbeing. Climate change is resulting in warmer temperatures generally, shorter winters, hotter summers, and more extreme weather everywhere. In Europe, in 2003, heat and air pollution caused in excess of 35,000 deaths. The Canadian Medical Association estimates that Canada’s air pollution is responsible for 21,000 premature deaths a year and 92,000 emergency room visits. Beijing has one of the worst smog ratios in the world and pollution from coal fired power plants has meant that 90 percent of Chinese citizens are exposed to at least 120 hours of unhealthy air annually. Climate change could be responsible for as many as 250,000 deaths annually according to the Lancet medical journal.

Norman Bethune loved the clean air and beautiful woods of the Canadian North. He was an outdoorsman as well as being a specialist in surgery and respiratory medicine. He would instantly connect the bad conditions of smog with the rising incidence of strokes, heart disease and lung cancer, just as he connected tuberculosis with bad sanitation. He would urge China to take the lead in guiding both itself and the world towards planetary health in order to ensure our individual health.

Wendell Berry, an American poet and farmer, has it right when he argues, “We have lived our lives on the assumption that what was good for us was good for the world... Now we must live by the contrary assumption that what is good for the world would be good for us.” Were he still with us, Bethune would wholeheartedly support that idea but he would also employ his incredible energy to help make a sustainable planet a reality. Adrienne Clarkson concludes her excellent biography by stating that a billion and a half Chinese know Bethune as Bai Qiu En – the light who pursues kindness. Today Bethune would be known as the light leading us towards better planetary health.