On 10 October 2018 in Rovaniemi, Finland, in conjunction with the Arctic Biodiversity Congress, the InterAction Council gathered a High-Level Expert Group to discuss the Arctic. The meeting focused on three themes: biodiversity, cooperation, and development. There was also time and consideration given to the unique role of Indigenous peoples in the region. Given the InterAction Council’s interest in global ethics, it is worth exploring how Indigenous rights are being annunciated in this region, in light of the increasing interest of the global community, as well as the pronounced impact of climate change.

As powerfully stated by one of the participants, “The Arctic is the last region of the world where there is an opportunity for the global community to get things right.” The Arctic is warming at twice the rate of the rest of the world. Every participant at the meeting referenced climate change, and the urgency needed to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement to reduce emissions and also to adapt to the warming that is already underway. The most recent report of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was released as the experts’ group was meeting. In the October 2018 report, the world’s leading climate scientists called for nations to cap the rise of global temperatures at 1.5 degrees Celsius. If this goal is not met, extreme weather will further intensify with major risks to humanity that include ice melt, flooding and punishing heat.

The Arctic has been the home of Indigenous peoples since time immemorial. Indigenous peoples in the Arctic have been increasingly asserting their rights, including to self-determination, and the Arctic has been where some of the most innovative approaches to shared governance between Indigenous peoples and state authorities has taken place. This ranges from the Saami parliaments of Norway, Sweden, and Finland, to the constitutionally enshrined right to self-government offered by the modern land claims in Canada.

Indigenous peoples in the Arctic are working to design new forms of government that are based on their culture and traditions, recognising that colonialism has interrupted the structures of societal control that existed before contact. Indigenous peoples are rebuilding their societies and trying to figure out how to do this using some of the structures of modern societies. As one participant explained, “the structures of our lives are not new and have been developed within our societies over centuries, what is new is the recognition.”

The creation of new governance structures has not been seamless. There are some within the Alaska Native community who espouse the view that the Alaska Native Land Claim and the Indian Reorganization Act, rather than positively contributing towards Indigenous rights, has created division and tension within communities.

Greenland, alternatively, is exploring the potential for independence and challenges the world to consider, “how can a people afford self-determination?”

It was also suggested that Indigenous peoples, “are the most regulated people on Earth.” While international instruments, such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, have been positive in its recognition of Indigenous rights, there remains other international vehicles where there has not been the same consideration of Indigenous issues. This includes the World Intellectual Property Organization, which has been resistant to recognize the collective intellectual property rights of Indigenous Knowledge.

Arctic Indigenous peoples have been active in global processes, aiming to give greater recognition to their rights. Many Arctic Indigenous nations are active in the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Peoples. They share their experiences with Indigenous nations from other regions of the world, many of whom have not yet received the same level of recognition of their inherent rights.

There are a number of international mechanisms and organizations that are mandated to specifically look at Indigenous issues. It was suggested that such a segmented approach is not effective and that there needs to be increasing consideration of how Indigenous rights are impacted across issues. This is particularly true for mechanisms that address climate change, as Indigenous peoples are being significantly impacted by a warming world, despite the fact that they have least contributed to the causes.

For some, climate change in the Arctic offers new opportunities for economic development. The question was raised about whether the Arctic needs to be integrated into the global economy. For example, as one participant explained, “Alaska salmon is known worldwide, but it is a keystone species for our culture and communities.” It was recognized that there are both drawbacks and benefits to increased economic activity in the region.

The contribution of the Arctic region to national GDPs varies significantly by country. For example, the Arctic contributes to approximately twenty per cent of the GDP of Russia, compared to seven per cent for Finland, and less than one per cent for Canada.

Of particular note is the difficulty for regulators in evaluating mitigation strategies for companies in extractive industries. In Canada there is co-management of lands and resources. Co-management is the sharing of administration over management of resources between Indigenous governments and other levels of public government, which means that Indigenous governments are directly involved in licensing, permitting, and environmental impact assessment processes. As part of these reviews, they evaluate mitigation strategies. However, mitigation strategies are based on minimizing the impact on the environment, as it exists today. What is known, though, is that even if strict measures are taken immediately, the impacts of the past actions will continue for at least the next fifty years. As a result, adaptation measures are integral, but there also needs to be new ways to evaluate mitigation in the face of such rapid change.

Indigenous peoples have a diversity of viewpoints on how best to achieve balance between conservation and economic development, as well as the impact of these decisions on Indigenous culture. Indigenous peoples are wrestling with the question of how to balance taking part in the modern economy, while maintaining cultural practices and teachings related to the role of lands and waters.

In addition, biodiversity services are not part of national accounts, causing the value of ecological services to be underestimated. Similarly, it is often overlooked that new technologies, which are intended to address climate change, will require resources in order to be developed. Paradoxically, to address climate change, there is a need for more mining of resources like cobalt, which is required to build electric vehicles.

The Arctic is also home to four out of ten of the world’s largest fish stocks and therefore a changing Arctic or resource economy has a significant impact on the food security of China, Japan, as well as North America. In 2018, the Arctic states, as well as several European and Asia supporters, agreed to a 16-year moratorium on fishing in the High Arctic. This is the first international resource management agreement to be based on the precautionary principle.

In contrast is the approach towards offshore oil and gas development in the Arctic. There is currently no technology that could respond adequately to a large spill in Arctic waters. Consequently, the perception is that companies are operating under the expectation that a spill will not happen or that they will develop a new technology before it does. Several global companies have pulled out of Arctic offshore oil development in the last few years.

An area of particular concern is the opening up of the coastal plain of the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge to oil and gas leases. The coastal plain is where hundreds of species, including the Porcupine Caribou - the largest terrestrial migration left on earth - have their young. There are real concerns about the environmental and societal impacts of this development, as well as the shift away from conservation and towards increased development in the Arctic by the US administration.

The lack of infrastructure in the Arctic is a major barrier to economic development. There have been calls to establish an Arctic Infrastructure Bank. The projected scale of shipping in the Arctic is unknown, with many contradictory estimates for future growth. What is known, is that increased shipping will affect the marine mammals that live in those waters and that protection is challenging in such a sparsely populated region. For example, the North Slope Borough in Alaska – home to just 9,500 people – is one of the authorities in charge of implementing the International Maritime Organization’s Polar Code across tens of thousands of kilometres.

China has developed an Arctic Strategy and has expressed that it does not believe that decision-making about the Arctic should fall within the exclusive purview of the eight Arctic states. Indigenous peoples are concerned about how their rights will be impacted and their voices heard with the increased interest of global superpowers in their region, asking “how do 112,000 Inuit across four states be heard when the Chinese government speaks?” Indigenous organizations persevere, despite the overwhelming human and financial capacity challenges that they face, to advocate for their rights and make positive progress towards addressing the challenges facing their communities. There is a role for government, industry, academia, and the philanthropic sector to support capacity-building initiatives that assist Indigenous peoples to participate meaningfully in the discussions that affect them.

Those who see integration of the Arctic into the global economy as positive argue that there needs to be closer regulatory harmonization across the region to address the need for sustainable development, minimize transportation costs through new infrastructure, and provide opportunities for economic diversification through increased access to communications. Proponents see the tariffs and sanctions imposed on Russia as a considerable barrier to trade.

Despite increasing tensions between Russia and the West, the Arctic remains a model area of cooperation. The Finnish Government has invited the other Heads of Government of the Arctic states to Finland for an Arctic Summit. So far, the United States has declined to participate, however, there are hopes that such a meeting could be convened in order to raise awareness of the challenges and opportunities of the Arctic to a global audience. There are hopes amongst Arctic Indigenous leaders that such a meeting will be inclusive of their leadership, following the example of the Arctic Council, where Indigenous peoples’ organizations participate alongside state governments.

Russia is often lauded as an “Arctic superpower,” given that half the territory and population of the Arctic resides in Arctic Russia and that, unlike the other Arctic states, the Arctic region of Russia is a key driver in the national economy. The Arctic also looms large in Russian domestic mythology about the national character. Yet there is another power that is showing increasing interest in the natural resources and shipping routes of the Arctic region, while demanding a larger role in decision-making about what is still considered by many to be an emerging region of global interest. That player is China. The inter-relationship between China and Russia is worth consideration. In response to the sanctions imposed by Western powers, Russia is increasingly collaborating with China on economic development projects, including in the Arctic. Indeed, the belt and road project will extend through Russian Arctic to Norway. There are concerns about how this relationship will continue to evolve and the potential impacts of geopolitics from outside the Arctic region spilling over to an otherwise peaceful and orderly part of the world.

Recommendations

- Call for an Arctic Summit of the Heads of Government of the Arctic region to discuss the critical issues facing the region at the highest political level.

- Encourage Arctic states to adequately fund Permanent Participant involvement in the Arctic Council, both to facilitate their participation in meetings, but also to enable research, expert review, and community outreach.

- Call upon the Government of the United States to cancel oil and gas leases in the Alaska National Wildlife Reserve.

- Develop new mechanisms to effectively evaluate corporate mitigation strategies in an era of rapid environmental change.

- Establish an Arctic Infrastructure Bank to assist Arctic communities with development of transportation, energy, and social infrastructure in the region.

- Call on states to urgently redouble efforts to meet the Paris Agreement goal of a reduction in emissions to keep global temperature rise to a maximum of 1.5 degrees Celsius, while preparing and implementing adaptation strategies for the global warming that is already underway.

Appendix A: Background on Indigenous Peoples of the Arctic

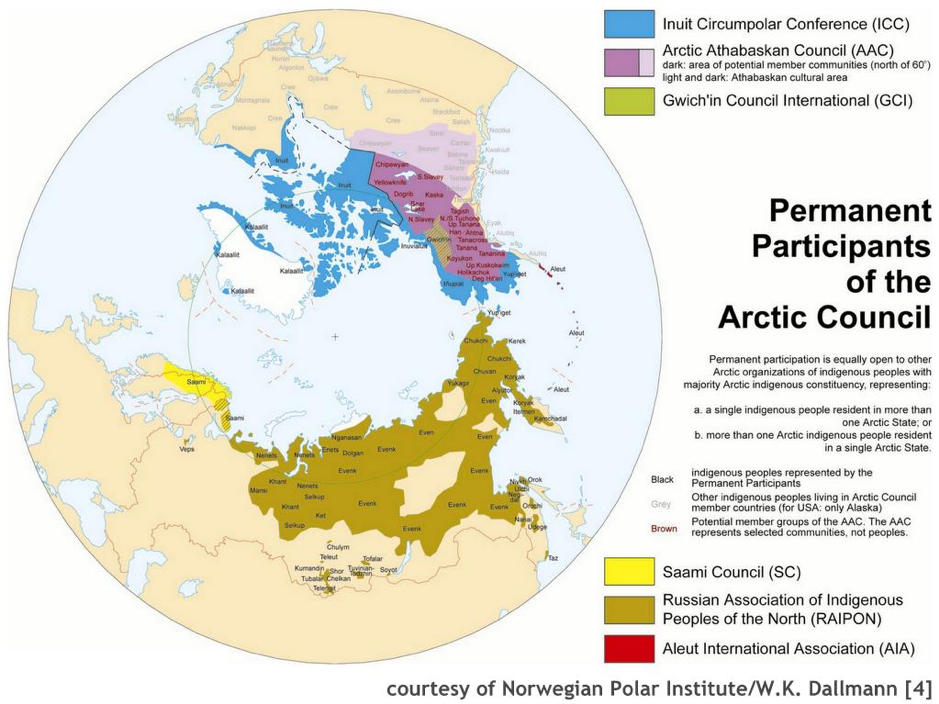

The Arctic is the homeland of several Indigenous peoples, including Aleuts, Athabaskans, Inuit, Gwich’in, Saami, and over forty Indigenous nations throughout the Russian North. Many Indigenous nations’ traditional territories transcend modern state boundaries. For example, Inuit live throughout Russia, Alaska, Canada, and Greenland, while the Saami homeland (Sampi) stretches across Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. The histories, cultures, and modern organization of Indigenous groups vary throughout the Arctic and are influenced by the time of contact, political organization of the state, and the geography of the lands and waters around them, as well as the animal resources upon which they rely.

Arctic Indigenous peoples are active at both national and international levels in asserting their inherent and defined rights. Uniquely, the Arctic Council - which is a high-level intergovernmental forum for the discussion of environmental and sustainable development issues in the Arctic – provides for the participation of six Indigenous groups alongside the national governments at the decision-making table. These organizations, known collectively as the “Permanent Participants,” are: Aleut International Association, Arctic Athabaskan Council, Gwich’in Council International, Inuit Circumpolar Council, Saami Council, and the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North. Many of these organizations also participate actively in United Nations and other international fora.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was passed by the General Assembly in 2017. UNDRIP recognizes, for example, the right of Indigenous peoples to free, prior, and informed consent,when development occurs within their traditional territory.

The rights framework within each of the Arctic states varies, but are generally considered to be some of the most progressive governance frameworks for Indigenous peoples throughout the world. That being said, there remains significant challenges for Indigenous peoples fully exercising their rights, as well as achieving socio-economic indicators on par with the non-Indigenous populations of their respective countries.

Highlights of the evolving governance systems throughout the Arctic, include:

- Alaska Land Claims Settlement Act (1971), transferred titles to 120,000 square kilometres throughout Alaska to twelve Alaska Native Corporations and over 200 Alaskan Native Villages, in exchange for extinguishing future claims.

- Throughout the Canadian Arctic, modern treaties (also known as Land Claims Agreements) were settled between Indigenous peoples and the Government of Canada that give expression to the Indigenous rights enshrined in Section 35 of the Canadian constitution. The Land Claims provided surface, sub-surface, and title land ownership to Indigenous nations. In addition, they provide for the transfer of decision-making authority under self-government and the sharing of decision-making with the federal and territorial governments through co-management of natural resources. Nunavut, where the population is 85 per cent Inuit, chose a public form of government; rather than Indigenous self-government, and in 1999 a new territorial (similar to provincial) government was created.

- In Norway, Sweden, and Finland, there are Saami parliaments, which are directly elected by Saami to address issues that are of their concerns. The parliaments also perform administration services for programs affecting Saami.

- Russia remains an outlier in some respects to the trend of progressive Indigenous relations with the state. Russian Indigenous peoples are recognized by the state if their population is less than 40,000 and the legal framework is patchwork depending on the sub-national region where they live, as well as the level of economic development potential on their traditional lands.

Despite these hard won rights, Indigenous peoples throughout the Arctic struggle with significantly lower socio-economic indicators than their non-Indigenous counterparts. Even in G7 countries – particularly, the United States and Canada – Arctic Indigenous peoples continue to live in poverty akin to third world conditions with higher rates of diseases, poverty, incarceration, and lower levels of educational attainment. The legacy of colonialism and racism remains strongly evident throughout Circumpolar Arctic Indigenous communities. However, in some countries, such as Canada, there is an increasing awareness by the government – and some would argue the general public – that such circumstances cannot persist, with increased focus towards reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians, supported by both government, community, and individual actions.

Appendix B: Map